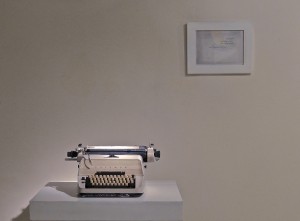

We increasingly encounter more artists competing for a more delicate form of informing others about their manifesto-like statements. A persuasive manifesto should detect people’s sensitivities and press upon them, presenting this pressure natural and introducing what the manifesto calls for as the only way to escape such an everyday torture. Hence, it is excusable if a manifesto is incoherent, and includes sliced up sentences and influential propositions creating a collage of ‘important’ facts in reader’s mind. This might be regarded as the power of a statement if when read to the middle, the reader already feels petrified, both hating his environment and frightened by it. In the end, he would definitely ‘take action’, and often, this is only thing that is asked of the reader, to merely ‘do’ something. This work by Mona Agha-Babaei aimed at presenting a manifesto. Its minimal atmosphere and the excessive whiteness which made the installation seem protruding from the gallery space and walls, had formed a mysterious aura around the typewriter. The aura called the viewers to approach it and interact. The buttons when pushed slightly produced the sound of a gunshot and made the whole experience different. This exactly is the moment when the audience is expected to have read half of the manifesto and be frightened. But, with by the help of a short text–which actually is a detail of the installation–on the wall beside the machine, the interpretation of the work became multiple, actually the artwork and its narration twisted within themselves. The text is uncanny–and its antiquity helps dazzle the audience even more– but it simultaneously situates the reader/spectator in the position of murderers as well as victims. The work first defines the audience as those who compose an era and hence its history, but then threatens him with passivity and destruction, with the danger of being buried under a mass of defining visions contradicting one another, visions of a local contemporaneity. However, the terror addressed in this work and its accompanying experience, does not stem from such a definition of the audience, rather because it is able to provide such a vision; the fact that the work has the ‘power’ of doing so, the power which its possession, is often supposed obvious and ordinary; a wrong supposition.